Below is a copy of the proposal submitted to the Special Committee on Electoral Reform on October 6, 2016. You can download a copy of the proposal here.

SUMMARY

This proposal, submitted to the Special Committee on Electoral Reform (“ERRE”), is for a uniquely Canadian and achievable Proportional Representation that incorporates the existing first-past-the-post system. We, like so many others, want every vote to count and want a Parliament that truly represents the will of Canadians, all Canadians. That is why we are submitting this brief that fulfills the ERRE’s mandate, and addresses both houses of Parliament.

What is BMP?

Bicameral Mixed-member Proportional (or “BMP”) brings something new to the table by broadening the scope beyond the voting system and tackling another seeming intractable Canadian political problem: the Senate. BMP reinvents the Senate by using it to bring proportionality to Parliament.

Given the importance of electoral reform, and Canadians’ discontent with the Senate, we encourage the ERRE to consider enhancing both houses of Parliament (thus “bicameral”). BMP solves these two issues with one reform.

How BMP works

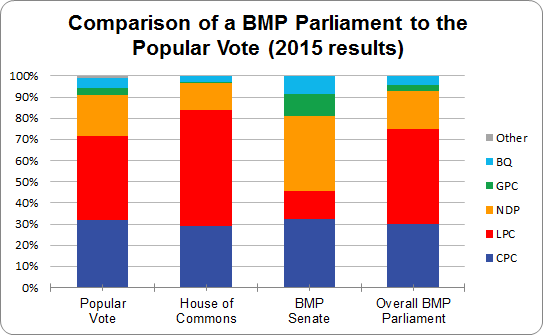

BMP is based on the Mixed-member Proportional system (or “MMP”) where a single legislature is created from a combination of “constituency seats” and “list seats”. Each constituency seat is represented by the winner of that constituency, or riding, from an election. After each constituency seat is determined, the remaining list seats are distributed to the parties that are underrepresented based on the popular vote. For example, if the Purple Party got 10% of the vote but only 5% of the constituency seats, they would be assigned enough list seats to make up 10% of the overall seats in the legislature.

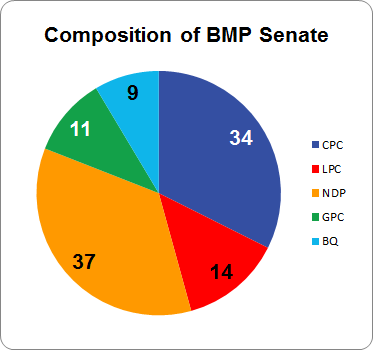

Under BMP, the 338 constituency seats in the House of Commons are awarded to a single MP for each electoral district, just as they always have been. BMP “list” seats are designated within the Senate to the parties who are underrepresented in Parliament based on the popular vote (principle 3 of ERRE’s mandate: accessibility and inclusiveness).[1] This creates proportionality across both houses.

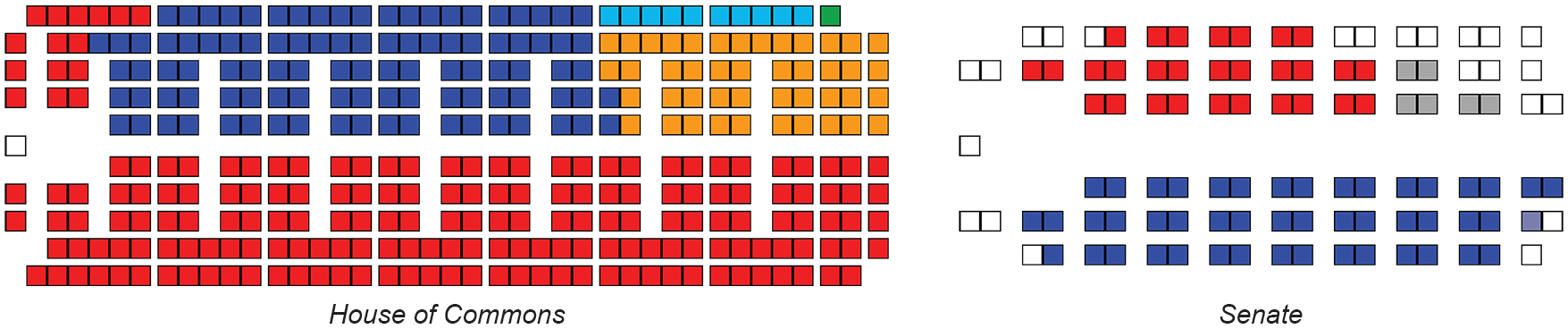

With BMP, Parliament goes from looking like this:[2]

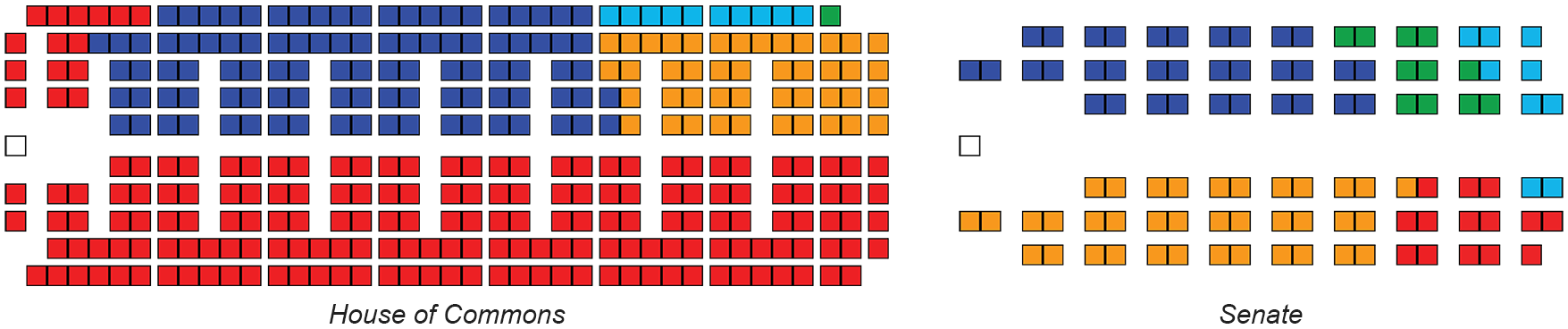

…to this:

BMP is an evolution of our trusted and traditional Westminster system. The big difference is that under BMP, the Senate is revitalised by speaking for the underrepresented. Canadians will gain an improved Parliament while keeping their familiar ballot.

Further, by using the Senate, BMP ensures that representation is proportional within the provinces and territories, as well as nationwide. This means that local minorities across Canada get their right to representation, be they NDP supporters in Western Canada or Conservative supporters in Atlantic Canada. With BMP, even though one house may be disproportional to the popular vote results of an election, proportionality is achieved throughout Parliament as a whole (principle 1: effectiveness and legitimacy).

WHY BMP?

Most other PR options before the ERRE, if not all, only address the House of Commons leaving half of Parliament still not representing the choices of Canadians. Many Canadians do not relate to the Senators that represent them.[3] It is easy to see why. Not only can one party gain 100% of the power with fewer than half of the votes in Parliament’s lower house, but Canadians have no influence in who represents them in the upper house. Every seat in Parliament under BMP is a reflection of Canadians’ will (principle 2: engagement). BMP reaffirms the Senate’s constitutional requirement to provide regional balance and representation on federal issues. It does all this without adding seats to Parliament or changing the voting method.

BMP also ensures greater stability than most other PR models. Under Canada’s current responsible government system, the government must resign if it loses the confidence of the House of Commons. The odds of this occurring are higher if the House of Commons alone were elected using conventional PR. But there is nothing in the Constitution, nor is it a constitutional convention that the government must resign if it loses the confidence of the Senate. The worst that could happen is the Senate could refuse to pass House of Commons’ Bills they feel need more work, and vice versa. But this is exactly what should happen within a government that represents various interests. To pass both the House and Senate, a Bill would normally have to satisfy more than one party, creating legislation that is more collaborative and reflective of Canadians’ diverse perspectives (principle 4: integrity).

BMP also ensures greater stability than most other PR models. Under Canada’s current responsible government system, the government must resign if it loses the confidence of the House of Commons. The odds of this occurring are higher if the House of Commons alone were elected using conventional PR. But there is nothing in the Constitution, nor is it a constitutional convention that the government must resign if it loses the confidence of the Senate. The worst that could happen is the Senate could refuse to pass House of Commons’ Bills they feel need more work, and vice versa. But this is exactly what should happen within a government that represents various interests. To pass both the House and Senate, a Bill would normally have to satisfy more than one party, creating legislation that is more collaborative and reflective of Canadians’ diverse perspectives (principle 4: integrity).

One of the many benefits of BMP is that voting can stay exactly the same. Canadians can make their choice on a single ballot when voting for a local MP (principle 5: local representation). With BMP, that same ballot lets Canadians choose all of their representatives, making every vote count.

How Would Senators be Selected?

Senate numbers are determined for each party deserving of additional representation in serving the goal of proportionality across the combined bicameral seat count for each province or territory. They could be selected from the best finishers in the election. Even independents finishing a strong second in their riding could, in theory, become Senators.

What About Existing Senators?

Senators can agree to voluntarily resign when Parliament dissolves.[4] However, the BMP system can still improve the balance of Parliament with as few as 20 open seats even if incumbents remain (see Appendix D).

Sober Second Thought

According to the Supreme Court of Canada, the framers of the Constitution intended Senators to have “security of tenure” giving them “independence in conducting legislative review.”[5]

While this may have been the framer’s original intent, a majority of Canadians no longer support this concept.[6]

Arguably, Senators from different parties with varying viewpoints could provide healthier legislative review. BMP enhances the Senate’s “sober second thought” with a shift from independence to accountability.

Is a Constitutional Amendment Required to Implement BMP?

The most effective way to implement BMP would be to amend or repeal sections 24, 29 and 32 of the Constitution Act, 1867. These amendments would have to be done under the 7/50 procedure (the approval of Parliament and seven provinces making up at least 50% of the population).[7] There are a number of ways BMP could be implemented in the interim. For example, while constitutional negotiations are taking place a Prime Minister committed to BMP should put a freeze on appointments, and then undertake to fill all Senate vacancies as informed by BMP election results.[8] This is a sample of how BMP can be implemented with flexibility.

We recognize any matter involving the Constitution can be difficult, but if better government is possible then we should strive for it.

CONCLUSION

Without any requirement to change the ballot, electoral districts, or the tenure of current Senators, BMP would be among the simplest available reforms. It will also produce strong and stable governments that are held in check by a Senate empowered with new relevance. Canadians will know that their vote will contribute to the composition of Parliament as a whole, reducing strategic voting and voter apathy.

The principle of BMP is to improve proportionality of the overall parliament, hence bicameral, relative to the vote. A BMP Senate would make a Parliament much closer to the popular vote.

Yes, BMP might require some constitutional amendments, but the Constitution is a “living tree” meant to change with “the realities of modern life.”[9] What is ultimately needed is for different levels of governments to work together to give Canadians a representative democracy. BMP creates a Parliament that reflects Canadians’ interests with a made-in-Canada solution, and it can all be achieved with the same, simple ballot.

If you would like additional information, please see the Appendices and visit our website at www.bmp-bpm.ca.

End Notes

- ^ House of Commons, Journals, 42nd Parl., 1st Sess., No. 67 (7 June 2016).

- ^ This is the seat distribution the day of the 2015 federal election; see Parliament of Canada, Elections, (Ottawa: Library of Parliament database, n.d.), online: Parliament of Canada (last visited 5 October 2016).

- ^ “Two-in-three Canadians say the Senate is “too damaged” to ever earn their goodwill” (3 May 2016), online: Angus Reid Institute (last visited 5 October 2016) [Angus Reid].

- ^ Constitution Act, 1867 (U.K.), 30 & 31 Vict. c. 3, s. 30, reprinted in R.S.C. 1985, App. II, No. 5.

- ^ Reference re Senate Reform, 2014 SCC 32 at para. 79 [Senate Reference].

- ^ Angus Reid, supra note 3; Daniel Bitonti, “CTV Poll: 69% of Canadians don’t believe Senate is useful”, CTV News (1 January 2014) online: Bell Media.

- ^ Senate Reference, supra note 5 at paras. 71-85.

- ^ This type of scenario should be constitutional as per the Senate Reference, supra note 4 at paras. 50-67.

- ^ Edwards v. Attorney-General for Canada, [1930] A.C. 124 (P.C.), at p. 136; Reference re Same-Sex Marriage, [2004] 3 S.C.R. 698, 2004 SCC 79, at para. 22.